OSHA’s 2024 HazCom Final Rule

The UN published GHS Revision 7 in 2017, and it didn’t take long for OSHA to begin planning to use it as the basis for its next HazCom revision. OSHA mentioned its intention to update the HazCom Standard to align with GHS Revision 7 during public meetings in 2018 and 2019, and in 2020, they included their planned proposed rulemaking on their Regulatory Agenda. OSHA finally published their Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) to update the HazCom Standard in the Federal Register on February 16, 2021.

The public comment period for the NPRM ran until May 19, 2021. OSHA also held a public hearing in September 2021 to gather additional commentary from stakeholders on various elements of their proposed changes. But many tentative deadlines came and went before OSHA finally published a final rule in Federal Register on May 20, 2024.

At a high level, OSHA’s final rule brings the following changes to the HazCom Standard:

New Classifications for Aerosols, Chemicals Under Pressure, Desensitized Explosives, and Flammable Gases

The final rule makes several changes to the ways that certain chemicals are classified to align with the classification criteria of those chemicals in GHS Revision 7, or in the case of chemicals under pressure, GHS Revision 8.

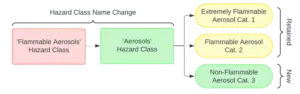

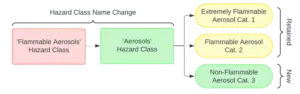

Aerosols: OSHA’s final rule is following GHS Rev. 7 (UN GHS, 2017, Document ID 0060) by renaming the existing Flammable Aerosols hazard class “Aerosols” and expanding Appendix B.3 to include non-flammable aerosols, while retaining flammable aerosols. Non-flammable aerosols will now be under a newly created Category 3, while flammable aerosols will continue to be under Category 1 or Category 2.

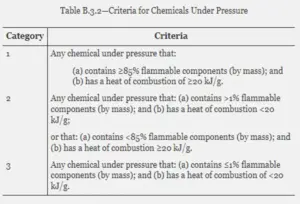

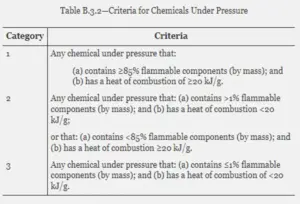

Chemicals Under Pressure: OSHA has adopted a new hazard category, chemicals under pressure, within the aerosols class following classification criteria in GHS Revision 8. These revised classifications also change some associated hazard information, including hazard pictograms and hazard and precautionary statements.

The term “chemicals under pressure” refers to liquids or solids in a receptacle (other than an aerosol dispenser) pressurized with a gas at a gauge pressure of >=200 kPa (29 psi) at 20°C / 68°F. A product classified as a chemical under pressure cannot also be classified as an aerosol, a gas under pressure, or a flammable gas, liquid, or solid. In general, chemicals under pressure typically contain 50% or more by mass of liquids or solids whereas mixtures containing more than 50% gases are typically considered as gases under pressure.

In finalizing the chemicals under pressure hazard classification, OSHA has included all three categories as defined in Table 2.3.3 in Rev. 8 and largely included the hazard communication elements in Table 2.3.4 in Rev. 8 (Document ID 0065, p. 62) in Appendix C.16. The table below shows the chemical under pressure categories and associated classification criteria adopted in the final rule.

Desensitized Explosives: OSHA’s final rule is following GHS Rev. 7 (UN GHS, 2017, Document ID 0060) by adding a new physical hazard class for desensitized explosives. There will be 4 categories (1,2,3, and 4) within this new hazard class in new Appendix B.17.

Desensitized explosives are explosive chemicals treated to stabilize the chemical or reduce or suppress explosive properties. To be classified as a desensitized explosive, a chemical must be a solid or liquid, must remain homogenous with its desensitizing/stabilizing agent, and cannot also be classified as an explosive, flammable liquid, or flammable solid.

Desensitized explosives pose explosive-equivalent hazards in the workplace when the stabilizer is removed or inadvertently lost, either as part of the normal work process or when the chemical is stored. Therefore, it is urgent that chemical manufacturers identify and appropriately communicate hazards, including the importance of the stabilizer.

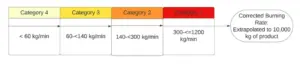

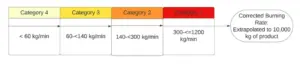

The chart below shows the four categories of desensitized explosives as adopted by the final rule. The “burning rate” in the chart refers to its combustion rate as determined by testing the product in packaging as stored and used. Note that the upper range of Category 1 is 1200 kg/min. This makes sense considering the concept of desensitized explosives, since there needs to be an upper limit on the burn rate of a chemical for it to be able to be stabilized. In the chart, products with a burn rate greater than 1200 kg/min would be explosives.

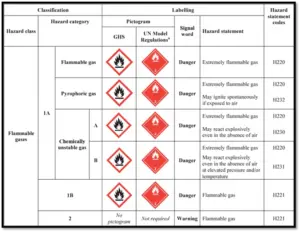

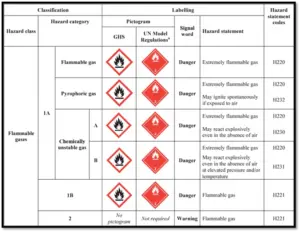

Flammable Gases: OSHA’s final rule subdivides Category 1 of this hazard class into two subcategories (1A and 1B), requiring pyrophoric gases and chemically unstable gases to be classified as Category 1A. OSHA maintains that these changes will provide more detailed information about flammable gas hazards and align with GHS Rev. 7 (UN GHS, 2017, Document ID 0060). Under HazCom2012, products classified as Flammable Gas Category 1 could have a wide range of flammability properties, so this update to subdivide category 1 will allow more specific and concise hazard communication information relative to a flammable gas’s intrinsic properties.

The image below show OSHA’s updated flammable gas categories and associated hazard communication elements:

New Labeling Provisions for ‘Small’ and ‘Very-Small’ Containers

OSHA’s final rule incorporates guidance previously provided by OSHA for labeling “small containers” into the text of the Standard, defining a small container as 100 mL or less in volume. Paragraph (f)(12) in the revised standard, addressing labeling of small containers, specifies that chemical manufacturers, importers and distributors can include less information on the shipped label when they can demonstrate that it is not feasible to use pull-out labels, fold-back labels or tags to provide the full label information as required by paragraph (f)(1).

OSHA’s final rule also allows chemical manufacturers, distributors, or importers to provide only a product identifier on “very small containers” (3 ml or less) if they can demonstrate that a label would interfere with the normal use of the container, although they’d still need to include the full shipped container label information on the outer packaging.

However, manufacturers of chemicals in both small and very small containers must include the following information on the label of the immediate outer package:

- Full shipped container label information for each hazardous chemical, and

- A statement that the small container(s) must be stored in the immediate outer package when not in use.

OSHA established these requirements to balance out the allowances for chemical manufacturers to use less information on the immediate chemical container, to ensure that end users can easily access the full range of information normally present on the shipped container label.

Updated Hazard and Precautionary Statements for Clearer, More Precise Hazard Information

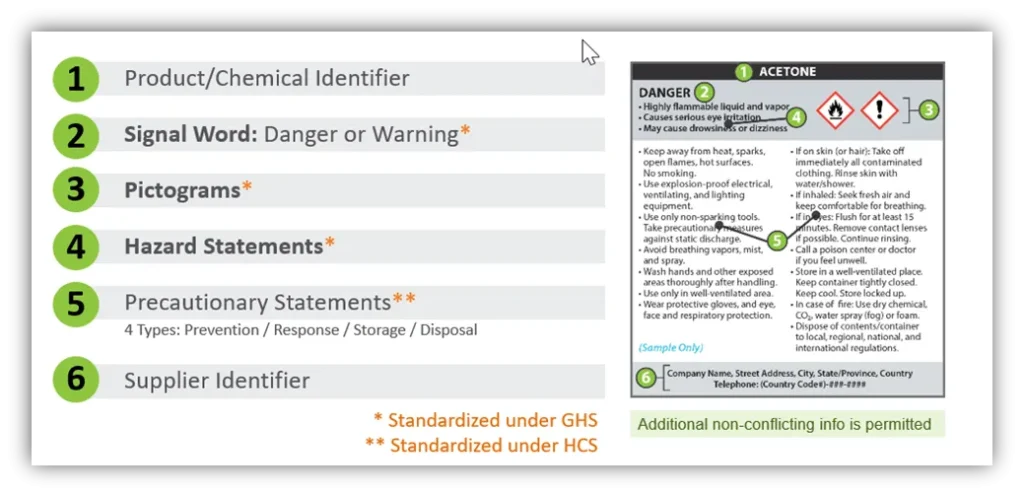

OSHA’s final rule revises several hazard and precautionary statements to align with GHS Rev. 7. The rule adds a new paragraph C.2.4.7 noting that “precautionary statements may contain minor textual variations from the text prescribed elsewhere in appendix C (e.g., spelling variations, synonyms or other equivalent terms), as long as those variations assist in the communication of safety information without diluting or compromising the safety advice.”

HNOC Pictogram Allowance

The final rule updates Appendix C to allow the exclamation mark pictogram for Hazards Not Otherwise Classified (HNOCs) to appear on SDSs, and labels. OSHA lays out precedence information when using the pictogram and requires the words “Hazard not otherwise classified” or the acronym ‘HNOC” below the pictogram, if used to denote an HNOC. This allowance reflects OSHA’s agreement with Health Canada to permit exclamation mark pictogram for HNOCs and helps US to better align shipped container labeling with Canada.

Updating Labeling Requirements for Packaged Containers “Released for Shipment”

OSHA’s final rule states that manufacturers, distributors, or importers that become aware of new significant hazard information would not need to relabel chemical products already released for shipment, as previously required.

Over the years, many stakeholders informed OSHA about the difficulty, and danger, of accessing shipped containers that had already been “released for shipment,” meaning they’d been bound together or secured to pallets. Suppose a manufacturer learns of new hazard information about a chemical that’s already been bundled up for shipment into commerce. Employees would need to potentially cut apart binding, climb up onto palletized shipments, and physically struggle to access the shipped labels on individual containers. These efforts could lead to many bad outcomes, including employee injuries or spills of hazardous chemicals. That’s why OSHA proposed to eliminate the requirement for chemical manufacturers to relabel packages released for shipment in their 2021 NPRM. Stakeholders supported this regulatory change, so OSHA made it official in the final rule.

However, OSHA has not finalized its modified requirements exactly as written in the NPRM, and most notably is not requiring a “released for shipment” date on the label. OSHA had originally maintained that requiring chemical manufacturers to provide the date a chemical is released for shipment on the label would allow manufacturers and distributors to determine their obligations more easily under paragraph (f)(11) when new hazard information becomes available. Stakeholders objected, citing practical concerns about lack of space for a “released for shipment” date on the label, costs of updating printed label stock, or how to determine the date to use. Based on this feedback, OSHA dropped the “released for shipment date” label requirement from the final rule.

Labels for Bulk Shipments of Hazardous Chemicals

OSHA’s final rule codifies an allowance for bulk shipments originally provided via a 2016 joint memorandum, clarifying that labels required under OSHA’s HazCom Standard and by Department of Transportation (DOT) Pipeline Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) can appear on the same container.

OSHA and DOT originally issued the 2016 joint memorandum because while both agencies have policies that containers should not be labeled with any labels required by regulatory agencies other than their own, they were aware of situations in which a manufacturer or distributor might want to put both kinds of labels on the same package. For example, a tanker truck or railcar that’s stationary at an employer’s worksite would need to be labeled with HazCom shipped container labels, but the same vehicle would be subject to DOT/PHMSA regulations while in transit. The 2016 joint memo allowed the same container to bear both kinds of labels and the final rule formalizes the allowance within the HazCom Standard.

According to OSHA’s final rule, labels for bulk shipments may be:

- On the immediate container (as shown in the image above), or

- Transmitted with shipping papers, bills of lading (BoLs), or electronic means

Concentration Ranges and Confidential Business Information (CBI)

In the 2021 NPRM, OSHA proposed several changes to paragraph (i) of HazCom, describing the conditions under which a chemical manufacturer, importer, or employer may withhold the specific chemical identity (e.g., chemical name), other specific identification of a hazardous chemical, or the exact percentage (concentration) of the substance in a mixture, from the SDS as a trade secret, or CBI. OSHA proposed to allow manufacturers, importers, and employers to withhold a chemical’s concentration range as a trade secret, which had not previously been permitted, and to clarify that it is Section 3 of the SDS from which trade secret information may be withheld.

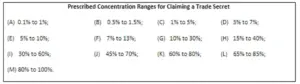

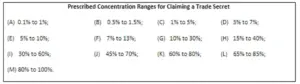

After considering all stakeholder feedback, OSHA finalized its proposed CBI changes mostly as proposed but added a new paragraph (i)(1)(vi) allowing the use of narrower ranges than those prescribed in (i)(1)(iv) and (i)(1)(v). The range must be fully within the bounds of a prescribed range listed in (i)(1)(iv) or fully within the bounds of a combination of ranges allowed by (i)(1)(v).

The table below shows the prescribed concentration ranges OSHA is adopting:

Classification Based on “Intrinsic Properties” and Known or Reasonably Anticipated Downstream Uses

OSHA’s final rule states that, “hazard classification must include hazards associated with the chemical’s intrinsic properties including: (i) a change in the chemical’s physical form and; (ii) chemical reaction products associated with known or reasonably anticipated uses or applications.” The final rule clarifies that hazards from a chemical reaction (the actual GHS-based classifications) belong in Section 2(c) of the SDS, and hazards from changes in intrinsic and physical form belong in 2(a).

Stakeholders during the public comment period for the 2021 NPRM possibly expressed more concerns about this provision than any other, especially because of the NPRM’s original text referencing “normal conditions of use” and “foreseeable emergencies” seemed too broad. Some chemical manufacturers worried that they’d need to factor in every possible downstream use and scenario when classifying a chemical, and that was effectively impossible. OSHA’s updated text in the final rule is an attempt to delineate the narrower expectations for manufacturers to classify chemicals only based on “known or reasonably anticipated uses.”

OSHA provides the following useful summary in the text of the final rule:

“In conclusion, OSHA agrees with commenters that it would not be possible for every manufacturer, importer, and distributor to be aware of every single use or application of its products, and the agency is not requiring these entities to do the kind of intensive investigations that many of the commenters described as infeasible. Additionally, regulated parties will not immediately be aware of all uses when new products are developed or when there are trade secret issues with downstream users. Similarly, OSHA would not expect a manufacturer to know every use of feedstocks (raw materials used to make other chemical products), starting materials or commodity chemicals, solvents, reactants, or chemical intermediates where there could be thousands of uses or the substances are used in downstream manufacturing to produce new chemical products. However, the agency concludes that manufacturers must make a good faith effort to provide downstream users with sufficient information about hazards associated with known or reasonably anticipated uses of the chemical in question. As discussed above, OSHA is finalizing language to make this clear, and to tie the classification obligation to either the manufacturer, importer, or distributor’s own knowledge or facts that the manufacturer or importer can reasonably be expected to know.”

Information Requirements for SDSs

OSHA has updated information requirements for SDSs, including addition of “particle characteristics” for solid products in Section 9 of SDSs.

The 2021 NPRM proposed that only manufacturers of solids would need to include “particle characteristics” information such as particle size (median and range) and, if available and appropriate, further properties such as size distribution (range), shape, aspect ratio, and specific surface area in the SDS. OSHA explained that they were trying to better align with GHS Revision 7, which includes an updated list of physical properties for chemical manufacturers to include in Section 9, and that characteristics such as particle size distribution were important determinants of hazardous properties, since particles less than 100 microns in size carried greater exposure risks, especially through inhalation.

The final rule adopts the “particle characteristics” requirement essentially as proposed in the NPRM. OSHA explained that the Standard does not require chemical manufacturers to conduct testing to determine particle characteristics, and that chemical manufacturers would not need to present particle characteristic information in a specific order.

OSHA’s final rule makes several other slight revisions to Section 9 requirements. For example, OSHA has added a parenthesis stating, “includes evaporation rate” in Section 9 (o), Vapor pressure.

Other minor changes include the term “viscosity” replacing “kinematic viscosity” and “physical state” replacing “appearance (physical state, color, etc.)”

Remember that OSHA has also finalized revised requirements for including hazards due to known or reasonably anticipated downstream uses in Section 2, and has stated that under some circumstances, importers may need to author new SDSs for products from foreign suppliers that didn’t come with SDSs containing domestic supplier contact information. OSHA has also made generally minor modifications to SDS Sections 8, 10, 11, and 14 that create a need for chemical manufacturers/responsible parties to, at a minimum, evaluate SDSs. Altogether, these changes will affect SDSs for many products.